READING LOG

“Books must be read as deliberately and reservedly as they were written.” –H.D. Thoreau…thank you, Leenie

“Reading fiction doesn’t help us escape the world, it helps us live in it.” — pithy tagline from the lovely and earnest Harry Potter & The Sacred Text podcast, and I’m applying it to nonfiction, too

“You have to know this, and it’s true with any art—you create it, you put it out there, and everybody perceives it through their own filter, the filter of their own experience. That’s a given.” —Bruce Cockburn, interview with WEXT’s Chris Wienk

First, a few words of explanation.

My usual habit is to read disparately, to shift gears. Because I’m so dazzled and heartened by the diversity in this world. It’s one way of participating in the diversity…I also like and appreciate that this habit is, obviously, mind- and heart-expanding.

I have posted my thoughts on amazon and I flirted with Goodreads, but I prefer to tuck my “reviews” (responses, musings) here with all my other stuff. Ultimately, it’s a record I’m keeping for myself, though I’m delighted if anyone else wanders in. Yes, of course, spoilers…can’t be avoided.

Being a reader has made me a writer, and also a better, and braver, writer. I would also like to add: for many years, first as a young bookworm and continuing into my college years as a lit major, I hesitated to have or share opinions about books. Part of that may have been my respect or awe for the authors, but in looking back I also think it had to do with lacking confidence or not trusting myself. How should I presume? Well. Now I’m older, I’ve done some living, I’ve done some writing of my own, and I’ve never stopped reading—and my responses and opinions are more evident to me. I understand that they are mine; your mileage may vary, etc. We all each of us have a voice, a mind, and a heart. Here I am, finding mine, better late than never. As for the filter of my own experience, well, every time I read a book, I change and grow, so my filter changes and grows.

And so here I track. I gather in the stories, I travel in the information, finding and following connections and insights. And still there are more thoughts and ideas and beings and things than I will ever visit or fathom. Water droplet, the sea; ages of air, notes I don’t hear. “There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

<SCROLL DOWN…MANY PAGES AHEAD…>

Farley Mowat, The Snow Walker

“The snow people know snow as they know themselves. In these days our scientists are busy studying the fifth elemental, not so much out of scientific curiosity but because we are anxious to hasten the rape of the north or we fear we might have to fight wars in the lands of snow. With vast expenditures of time and money, the scientists have begun to separate the innumerable varieties of snow and to give them names. They could have saved themselves the trouble. Eskimos have more than a hundred compound words to express different varieties and conditions of snow. The Lapps have almost as many. Yukagir reindeer herdsmen on the arctic coast of Siberia can tell the depth of snow cover, its degree of compactness, and the amount of internal ice crystallization it contains simply by glancing at the surface.

The northern people are happy when the snow lies heavy on the ground. They welcome the first snow in autumn, and often regret its passing in spring. Snow is their friend [shelter, transportation made easy/sleds, tracking of food/prey, food preservation…]. Without it they would have perished or—almost worse from their point of view—they would long since have been driven south to join us in our frenetic rush to wherever it is we are bound.”

As I finish and set down this slender paperback of 11 chapters, I wonder. I wonder if they are fiction, “stories”…though obviously the spirit is truth, information, insight (in this, respect, this book puts me in mind of Richard Powers’ The Overstory, which I read a while ago—review below). I wonder if the white Canadian author made them up or instead collected the indigenous tales while traveling way up there, and perhaps embellished or filled out, or with slightly changed details to protect privacy. I wonder at landscapes and peoples I have never seen, and their amazing resourcefulness.

I feel horror and woe at what “we” have done to them and their world; their remoteness did not shield them. This book came out nearly 50 years ago, in 1976; Lord knows what the state of things and people are up in northern-most (colonized-Canadian) territories, now. I shudder to think, presuming all the forces arrayed against them and their way of life portrayed here continued or accelerated, plus now the fast-advancing effects of climate change up in the Arctic.

I do not wonder why the title of one of these, “The Snow Walker,” became the title of the collection—I’ll return to that here in a bit.

This collection of stories creates a picture of a world that is not only gone, but probably destroyed, ruined, and gone. I fear this, 50 years after its publication, when the forces of destruction were already bearing down on people who had lived and even thrived north of the Arctic circle. Fish, game, and deer (caribou) were caught and used to feed themselves and their sled dogs. Plants were also harvested and used as needed. They made their own durable, practical clothing and household implements. They had stories, songs, and a body of morals and beliefs based on the rhythm of the seasons and community cooperation. Also, as Mowat educates the reader, the cold and the snow was adapted to and indeed leveraged.

When white men began to encroach, it began to go to hell: white men’s opportunistic greed and white men’s diseases, of course, but also the objects and practices they introduced these people to, from Christianity to rifles to other shiny metal objects and different types of clothing and dry goods. The white men especially wanted, and paid top dollar or bartered food and other desirable items for, the pelts of the white-furred arctic fox. Until they didn’t. Also the Canadian government resettled the natives like pawns, for staking territory, not for their benefit, offering false promises. Including “we’ll convey you back home if you don’t like it,” a repeated lie.

“In the land of the Kablunait—the white men—things may be as you say…but this is not the land of the Kablunait. I do not understand how it is in your land. You do not understand how it is here. We know what we know.”

Again and again, the specter of starvation looms and kills. Especially in the winters when the expected caribou haven’t come through; the deprivation and desperation is awful. Babies and children weaken and die, pregnancies are lost, old people roll over in their bed of skins inside the shelter and breathe their last, or set out on a winter’s night, choosing to walk into their own cold overnight death rather than continue to suffer and to consume resources younger and healthier people need to survive. Hungry dogs the people cannot feed end up being killed and eaten. A family left behind inside an igloo shelter, women and children, get buried alive under a massive snowdrift that the men who went off in search of food or help cannot breach. It’s so awful and so sad.

One of these stories, “Walk Well, My Brother,” retitled “The Snow Walker,” was made into a film. I found it totally predictable. A white bush pilot with little knowledge of or interest in the landscape or people below his wings crashes but survives. He survives because the ill indigenous woman who he reluctantly took on as a passenger knows what to do in this landscape, for food and shelter. She saves his life. They do not shag. He learns and lives; weakened by sickness, she dies. I do not, however, think his odyssey is quite what is meant by “snow walker.”

In one harrowing story, a native woman clearly sees the damage being wrought and exhorts her people to resist and to return to the old ways. They try for a time, but the assaults on their livelihoods and spirits cannot be overcome; she begins to lose her mind and behave dangerously and erratically, including destroying valuable tools and supplies. Two young men, her son and nephew, are sent to subdue her while the rest of the frightened group cower at a distance—they end up killing her, seeing no alternative. White men learn of this, arrest them, hold a trial, and condemn the boys to a white-man’s jail far away. The young men, and those left behind, are bewildered and, worst of all, stripped of hope and dignity.

I did love the story about a pregnant husky, cut off from her animal and human community, and a lone wolf that helped protect her pups. He dies fighting off a wolverine while the dog mother is hunting. Shortly after the dog and her pups are reunited with their family group. Restoring the dog to the community is not like recovering a pet (though there is affection between the man and the dog); a litter of pups is an important, valued resource. The human sees and understands what happened. He tells his son:

“Maktuk, my son, in a little time you also shall be a man and a hunter, and the wide plains will know your name. In those days to come you will have certain friends to help you in the hunt, and of these the foremost shall be Arnuk [this dog]; and then my father will know that we received his gift and he will be at ease. And in those times to come, all beasts shall fall to your spear and bow, save one alone. Never shall your hand be raised against Amow, the wolf—and so shall our people pay their debt to him.”

It’s not that death doesn’t happen, it’s not that death is avoidable, even in the places and tales where white men haven’t yet wreaked damage and havoc. Death that’s a part of the circle of life is understood by these people, of course. Death that destroys ecosystems and cultures and breaks people is another, crueler matter.

The Snow Walker is referred to tangentially in a few of these stories, but is the title of one of them; to go out and meet the Snow Walker is to choose and greet your death. Death in darkness and snow on land that once sustained you and yours—that is the overall theme of these beautifully told, detailed, respectful, and heart-rending stories.

Eric Hansen, Orchid Fever: A Horticultural Tale of Love, Lust and Lunacy

“With thousands of orchids to study, hybridize, clone, and breed, it is not surprising how much money and time some orchid people will invest to satisfy their passion for these unusual plants. Power, prestige, and profit are among the more mundane reasons people get involved with orchids. There is a certain cache involved with owning something rare and beautiful, but curiosity, the love of exotic plants, the desire to create new hybrids and the drive to uncover complex botanical mysteries are the prime incentives that attract and hold the interest of true orchid lovers.”

The appeal and, indeed, the success of this book lies in the fact that the author is not an insider. He is a dogged investigative journalist, a smart fella, and an entertaining writer—and he brings back vivid pictures and commentary about this corner of the horticultural world. For a book on a specialty populated by everything from scientific researchers to collectors to propagators, some of them truly eccentric, it is surprisingly readable. The chapters are not long or belabored. Hansen keeps perspective, asks sharp questions and provides fair answers, and has a wonderful eye for detail.

I got a kick out of the sorts of things he noticed and described as he met orchid people. Stuff like this would never make the cut in a gardening magazine or scientific paper! Another reader might find his observations snarky or tangential, but hey, it’s all part of the picture and I daresay you won’t find these details in other books about orchids. For instance:

He visits a calm, polite, white-haired elderly lady in suburban Seattle. She shows him some of her favorite orchid houseplants. A cultivar called Magic Lantern, she declares, is a “bodice ripper!”

“Bodice ripper?” I took a closer look at the flower. The shiny, candy-apple-red staminoid that covered the reproductive organs was shaped like an extended tongue identical to the Rolling Stones logo. This shocking red protrusion nestled in the cleavage of two blushing petals then dropped down as if to lick the tip of an inverted pouch that looked like the head of an engorged penis. The blatant carnality of Magic Lantern was unmistakeable and I found myself wondering what sort of impression the flower was making on the old woman.

He gets a peek at orchid judging at a US orchid show, but not without some finagling. After talking to a variety of organizers, he’s finally “given clearance to bear silent witness to the proceedings.” Get a load of this:

A hush fell over the table and we sat in silence looking at the first plant. Surrounded by the grim-faced judges, the beautiful, fragile orchid looked naked and vulnerable. No one spoke at first as the judges focused their thoughts and concentrated on the task ahead.

“Nice lip,” ventured a student judge nervously.

“I’ve seen bigger,” said one of the accredited judges.

“Big, black, and beautiful, but the bugs been at it,” pointed out a third.

“Good gloss, but fatal flaws,” chimed in another.

“Cuppy, cuppy,” a woman snorted.

“Take it away,” mumbled a man across the table, as he went back to eating a chocolate-covered doughnut.

I was seated at a table of very hefty people and the contrast between the large bodies and the diminutive plant was extreme. No one could ever claim that orchid people are svelte. I found it ironic that these people, who were so utterly different from the orchids they judge, had spent so many years trying to establish what makes a perfectly formed flower. Huge hands with pudgy, nicotine-stained fingers reached out to caress the delicate blooms in a way that bordered on the obscene…

Another sample—this describes the expert judging of orchid fragrance:

With arms held tightly at his sides, Mr. Tokuda leaned toward the flower as if bowing at the waist, but with one foot set in front of the other. He was chewing gum rapidly as he took staccato sniffs from the flowers. He then began to shuffle his feet—slowly at first, but as he picked up the scent he became more animated until he was daring back and forth in front of the flower like a giant besuited insect nervously testing the fragrance.

Reading stuff like this, initially unexpected, made me giggle or hoot with pleasure. The truth is, Hansen was telling the truth!

But he’s serious about the topic, and tells all he sees and learns. I loved the chapter-ending picture he paints of a visit to 88-year-old researcher Dr. Gunnar Seidenfaden’s manor in the countryside outside of Copenhagen. “I want to end my life working on my book about Thai orchids. I would like to complete it by my 90th birthday,” the old botanist confides. The doctor is an example of what Hansen means by a true orchid lover (see extract above).

Gunnar emptied the bottle of port into our glasses. We had a toast to the success of what would be his final book and then drained the last sweet golden drops. It was after 3 am [Dr. Seidenfaden works starting at 10 pm each night] and I decided to let Gunnar get back to work. I went for a walk across the courtyard to where it led into the darkened fields. Looking back at the house I could see Gunnar at his desk, sketching, typing, and peering into his microscope…Watching him through that window, I found myself hoping he would be granted the blessing of time.

Hansen pursues orchid mania from many angles. Like many of the botanists he meets, has no patience for the uneven and ham-fisted application of CITES regulations (SWAT-team like raids of greenhouses to seize plants suspected of being illegally wild-collected and shipped; the confiscated evidence just dies in the hands of the authorities, such a sad waste). Allegedly these regulations are meant to suppress wild-collection. The rules don’t even distinguish between living and herbarium or preserved plants. A CITES official he interviews actually admits “we have no numbers, no idea” of the effectiveness of their rules and enforcement activities. Instead, basically, unfortunately, they’ve managed to suppress research and fruitful exchanges between experts. Let’s also bear in mind, for heavenssake, that orchid propagation and hybridization are presently more than sufficiently sophisticated (seeds and cuttings as well as—game-changing—tissue culture; greenhouse and lab techniques) that there would seem to be little need to ding or harass botanical researchers over some individual wild-collected plants.

Meanwhile, Hansen reminds, countless wild plants, including unknown and unnamed species, continue to succumb and/or go extinct, due to deforestation, development of roads, agriculture, hydro projects, etc. He tries to get answers or justifications from authorities, even foraying into the hallowed halls of Kew Gardens. But, well, it’s a stupid, counterproductive mess.

The book closes with him tagging along with Tom Nelson, a diligent orchid rescuer in Minnesota. These are terrestrial orchids, lady slippers (Cypripediums). Here the authorities don’t try to thwart this work. Some plants are plucked from the path of development, including peat-farming operations and road-widening projects; still, many are lost. I know enough to be left with a nagging question: neither our intrepid author nor Nelson mention that these orchids are dependent on specific mycorrhizal fungi in the soil for survival (was this not known at the time of this writing?). Unless each of those rescued plants came along with an ample soil ball, transplanting was likely to fail. Puzzling omission. It puts me in mind of all the orchids in the preceding chapters that I have little knowledge of—it takes a lot of research and trial-and-error to raise orchids from Thailand or Borneo or Brazil in captivity, never mind propagate them. Part of the appeal of orchids, I venture, is their mysterious and varied fussiness. Of course, avid growers will persist till they figure it out. Of that we can be sure.

My last reaction may seem beside the point but please understand, I’ve worked for magazines in the 1990s and I’m also the author of horticultural/botanical books. In this context, I am awed and a bit flummoxed by all the travel and research this book took. He does reveal that his trip to Turkey—to track down the allegedly aphrodisiac “fox testicle ice cream” made from indigenous orchid roots—was covered by National History magazine. That was an expensive expedition, and what was he even paid for the finished article, a few thousand bucks? Horticulture Magazine, my former employer, would never, ever have been in a position to fund any such thing. What about his trips to Kew, Paris, the Netherlands, Germany, Borneo? Is this guy independently wealthy, or a clever and frugal traveler? (Did he get grants?) I mean, what did he even get paid for this book, after investing many years and miles, published in 2000? I just cannot imagine how he worked this. SMH.

Glad he did, though—’twas a good read.

Frances Mayes, Women in Sunlight

“In comes Gianni, our local taxi driver. ‘The women have no men,’ he tells me. ‘They are on solo trips from the South of America, bringing a little dog, naughty, who peed in the carrier and barked all the way from the Rome airport.’

‘They have no car?’

‘No, but Grazia will sell them her mama’s Cinquecento as soon as the brakes are repaired.’

‘Is that legal?’ I know that it is not, unless they are registered residents. That Grazia. Maybe she has some scheme that gets around the law. I wouldn’t be surprised.

‘Why not?’

Why not is the local response to every preposterous proposition. Another thing I love.”

And thus I was swept into this tale of the three women from the South of America renting and later (spoiler) purchasing a ramshackle country house outside a charming and not-very-touristy Tuscan village. They originally met in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where they all happened to sign up for a tour of an “luxury retirement living community” on the outskirts, but were not persuaded. Two widows, one soon-to-be-divorced. Instead, they formed friendships and made a different plan. (Did they ever dodge a bullet!)

Their story is related by another American woman who is already present, in a nearby house, a writer. At first she is a bit standoffish, for she got here first. At first I thought she was older that our three heroines but it turns out she was not—our narrator is younger than them, but older than their children. She’s at work on a bio about a fifth woman character, her mentor Margaret, who passed away after a very productive and interesting life, but she becomes diverted by the new, alive arrivals.

The new arrivals, Camille, Susan, and Julia, are cast as a bit old-but-in-good-shape. I had to wince, as at least two of them are about my own age (just north of 60). Money for their Italian adventure is never an issue (which is not relatable, for me, but certainly keeps speed bumps out of the unfolding tale). They’ve had and have careers and savings, and their kids are fledged. That they would become so close so quickly, and undertake such an adventure together, speaks to the timing of their first meeting and to their shared social class but also to a forgiving flexibility that can come in later years. They all grow and change and, of course, bloom in Italy. Tensions are rare; they give each other a nice balance of space and support. Well, this is not utterly unbelievable, I muse as I ponder traveling with my own girlfriends or sisters.

Italian landscapes, light, and art are ardently described. For example:

Internet images of San Rocco occupied them over the months of planning, but they were in no way prepared the limpid light bathing the Renaissance facades of ochre, rose, sunflower yellow, and cream. The white marble steps leading up to the piazza’s church have over centuries worn to the soft glean of soap, and the tower bells ringing the quarter hour, the half hour, and the hour gong so resoundingly that their bones revererate.

On a jaunt north to Venice [personal aside, OH GOD,VENICE…I didn’t know when I picked up this book that once again I was going to visit Venice!/haven’t been there yet, long to go]:

One of the magic experiences on planet earth: zooming in an open boat across dark waters toward Venice.

And the food, lordy, the Italian food, not-to-mention-but-I-will the fresh pressed olive oil and the excellent regional wines red and white. I’m not going to quote any of that! Suffice to say there are gorgeous, mouth-watering cafe visits and snacks and desserts and feasts in nearly every chapter, to the point where the saturated reader rolls her eyes, c’mon, can it really all be that fabulous? Umm. I’ve been to Italy. It can.

Ah, perhaps it’s all a bit too perfect. Not one surly waiter, not one no-show contractor, not one aggressive tailgating driver? No side-trip-planning mishaps, despite not speaking Italian? (See the magical solution to needing a car in the extract above.) Well, they do weather being robbed—their rental house is ransacked while they are away exploring Venice and, among other things, jewelry of immense sentimental value is taken and never recovered. “Gypsies” were blamed, not surprising, but the racist assumption and the problem are not dwelt upon. The thieves ate some of their food and left behind three kittens. Kittens?!

Now I realize that the author also wrote Under the Tuscan Sun, which was made into a popular film. I believe the story there was a single, at-loose-ends woman went to Italy for diversion and fell in love with it all, bought a wreck of an old house, and worked to fix it up. Did she get a lover? Is she the same narrator as this subsequent book?, who did get a lover and even has the ultimately happy surprise of a late pregnancy at age 44 where nothing goes wrong. The father and she marry. The little boy is adorable. Their careers thrive.

As for the older women, their trajectory is similar, but perhaps with more nuance and flexibility. They aren’t blank slates; they’ve lived through a lot. Things from their past have to be let go, including a feckless husband and a beloved vacation home. One has a druggie daughter who has depleted her parents in every way; another has adopted grown daughters who decide to travel to China to try to find their birth parents (painful emotions for any of the parties don’t really surface—they later send their mom a “merry” text: “Couple of leads, dead ends, guess we’re stuck with you!”). One put her art in an attic long ago, and now rediscovers her urge, her inspiration, her power. Two gain lovers but of course not babies, nor new marriages. Once grasped, their independence is their joy.

So is this book lightweight escapist chick lit, a fairytale, a fantasy? Maybe it’s hard to utter a discouraging word or have dust-ups with housemates and neighbors when you’re so enchanted by the best of Italy—think of how well everyone gets along on a lovely vacation. Those delicious communal meals are a metaphor for seeking, creating, and savoring joy cooperatively, together—that’s not usually everyday life, but is worth imagining and manifesting when we can.

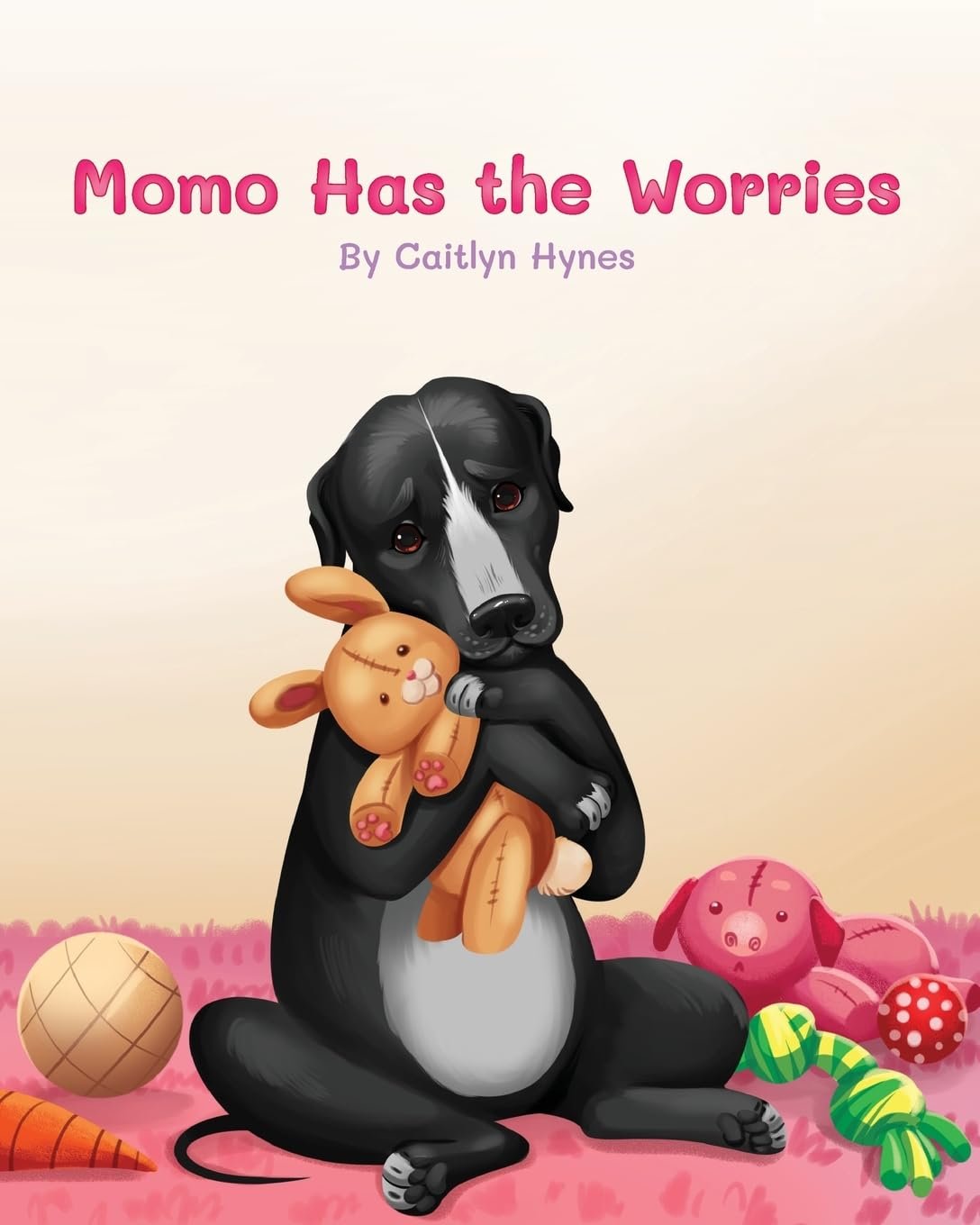

Caitlyn Hynes, Momo Has the Worries

“How do I know when I’m worried, you may ask? Identifying feelings is an important task!

My parents taught me how to do a full body scan. Checking in from head to toe helps me come up with a plan.”

The drawing on the front cover of this darling kiddie book is precious: wide-eyed, worried Momo the black dog is hugging his stuffed bunny, telegraphing both that he “has the worries” and that he is self-comforting.

Momo is a real dog, does look like the drawing, and—full disclosure—is a family member. The author is our nephew’s wife, “a proud mama, wife, animal lover, martial artist, baker, and mental health therapist who is passionate about empowering others to embrace their emotions and navigate them with self-compassion and care. She hopes to make mental health support accessible to young children and their loved ones using bibliotherapy…” Other readers would have no way of knowing this, but the drawings of the dog parents look like Justin and Caitlyn. I’m going to the guess the cats and the neighboring children are also based on real beings. Why not? Fun!

I adored reading aloud to my two sons when they were small and this book surely would have been in the pile. Caitlyn’s nailed the brief and lilting/rhyming text that makes kiddie books fun to read for the adults and fun to listen to for the little ones.

A couple other things I appreciate about this book: there’s realism, and the advice is sound. In particular, I notice that when worried Momo takes his full-body scan, the brain, the heart, and the stomach are drawn not as cartoons (say, a Valentine heart), but like the actual organs. Nice touch. Kids can handle this!

And the varied ways to deal with distress, anxiety, fear, and uncertainty are real and useful. After you take stock of where your body is reacting, you can: get comfort from hugs; do a breathing exercise; take a “mindful” walk; grab your stuffed animal; or go to your safe place alone and regroup. That’s a good collection of tools! Even at my age, I reflect that I’ve learned something useful here. To take a “mindful” walk is not to stomp around the block in a distracted, distraught haze, or to walk numbly until exhausted—instead, Momo recommends, we should open our senses. Don’t just move, don’t just look around. Stop, sniff, listen, feel the rain or wind or sunshine. As for retreating to a safe place, again, solid, and a tool too easy to forget or dismiss. Thank you, Momo. What a sweet and empowering little book!

J.A. Baker, The Peregrine

“A wrought-iron starkness of leafless trees stands sharply up along the valley skyline. The cold north air, like a lens of ice, transforms and clarifies. Wet ploughlands are dark as malt, stubbles are bearded with weeds and sodden with water. Gales have taken the last of the leaves. Autumn is thrown down. Winter stands.”

“Wild things are only truly alive in the place where they belong.”

“The sea breathed quietly, like a sleeping dog.”

Curled up on a sofa by a small light on a winter night, I must pause and place the bookmark in this deceptively slender little book. Because the dense writing is so continuously evocative and gorgeous that I need to slow down, savor, digest. What’s the hurry, really? It’s winter. Winter stands!

Which leads me to thoughts of why I plucked this book off the shelf. Well, it began when I took Kagan the dog on a chilly walk last week on the Erie Canal Trail. My mind and spirit often lament the lack of wildness around here—in the heart of Central New York’s farm country—but I can take him off the leash on that walk and he enjoys it, usually dashing ahead, occasionally detouring into the woods (young woods, sadly heavily infiltrated with invasive species), doubling back on the paved path to check on me. When I detected a raptor, not a large bird. Gliding and hunting. I took immediate note of how all other birds in our vicinity, the few winter stragglers, the gulls and ducks of the canal and river, had congregated and fallen into fearful silence or melted into shelter. The hunting bird soared and swooped up, then called out, three distinctive cries in succession. I committed the sound to memory and, as soon as we got home, searched on the Cornell birding website. A peregrine falcon.

Then I remembered I’d been gifted this book, and pulled it off the shelf. Time to learn.

But my interest in hawks preceded this moment. Up at the Nova Scotia place, last summer, on outings with the dog and even sometimes on my own, another species has captured my attention. I haven’t heard its call much but I’ve gotten clear views of it as it hunts along our side of the island. It was easy to identify, thanks to its distinctive white rump and fanned tail feathers—a marsh hawk, or harrier. Though not a sparrowhawk, Ged was the name I gave it. This winter, it was still around (I understand many area hawks migrate) and seemed to have a mate now. Once I saw one of them dive into the brushy meadow out back and fling back up within moments emphatically clutching its limp prey, a small rodent (rabbit? red squirrel?). Maybe hawks fascinate me not just because they are superbly beautiful, or because they are intriguing to watch in flight, but because also they are few. There, and actually, here, we have lots of crows, and when spring returns, there’ll be plenty of starlings, grackles, and sparrows. Up there, also, of course, there are also lots and lots of gulls and ducks of various kinds. Anyway, my point is, a hawk certainly stands out. Not a flock bird. In command of his body and his territory, his own agent, thrilling to watch.

OK, to this book, which was composed in the flat fenlands of eastern England. Baker set out to study his neighborhood’s peregrines (there are two at first, later a couple more) starting in autumn and is obsessively, with a scientist’s passion for and fidelity to observed details, tracking them daily. Mostly, it seems, on foot, which is a lot of effort and a lot of miles when you are a biped and your quarry has the advantage of flight. Occasionally by bicycle, I think, still arduous. This is not a wilderness area, but a valley with farms and, one assumes, roads, towns, and all the other features of development. The fields and waterways get frequent mention because they take up a lot of real estate. A seawall adjacent to an estuary is mentioned often, as are manmade features such as pylons that span the valley, and a chimney, posts, barns, roads and lanes. But the landforms, the mud, the trees, and the ebb and flow of water and wind, and the moods of the sky and clouds (yes, cold rain, it’s England; yes, gales, it’s the coast) dominate. As these things would to the birds.

Like me, he is drawn to the solitary but magnificent predator. He certainly describes and names lots of other bird species, but they are almost always in large flocks (gulls), or a small gang of a dozen, or even a few (jays, for instance) that congregate at times with their own kind. Every bird, every being, including our narrator, is cast and observed in relation to the whims and the habits and the hunger of the charismatic star, the peregrine.

Nor is the author idealizing or compartmentalizing this ecosystem. He encounters a bullet-slaughtered swan rotting in the marsh, notes an oil-covered sea bird grounded and dying on the beach, remarks on a bird splashing in a pond full of litter, debris, and sewage. Sheep graze, tractors work furrows, there is roadkill. From the opening chapter:

For ten years I followed the peregrine. I was possessed by it. It was a grail to me. Now it has gone. The long pursuit is over. Few peregrines are left, there will be fewer, they may not survive. Many die on their backs, clutching insanely at the sky in their last convulsions, withered and burnt away by the filthy, insidious pollen of farm chemicals. Before it is too late, I have tried to recapture the extraordinary beauty of this bird and convey the wonder of the land he lived in, a land to me as profuse and glorious as Africa. It is a dying world, like Mars, but glowing still.

In other words, the book is an elegy. Like Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire. (In which Abbey says “most of what I write about in this book is already gone or going under fast. This is not a travel guide, but an elegy. A memorial. You’re holding a tombstone in your hands. A bloody rock. Don’t drop it on your foot—throw it at something big and glassy. What do you have to lose?”) So swept up in the subsequent pages, I forgot Baker is also writing in the past tense (quick check: publication date is 1967). I spare a hopeful thought and fervent prayer for the survival of Ged and his mate on Long Island, Nova Scotia—I know we and neighboring landowners out there have no development (or harmful-chemical) plans, but I also know that the cascading effects of climate change are sifting into even that remote and relatively unspoiled place. I can, of course, do nothing for Baker’s birds but learn from them. And I can learn more about the Little Falls peregrine(s).

Asking around readily leads me to some information, for in a town this small, I’m not the only one who’s noticed them. In fact, I’m a couple of years late. I learn that a nesting pair moved from the Southside cliffs (where Kagan and I just saw one…so, have they moved back?) to the high, usused stone balconies on the tall Adirondack Bank building right downtown, where they evidently hatched four babies last summer while I was away in Nova Scotia. My friend Pooniel tells me “They've been in Little Falls for many years now. They've nested on the Adirondack Bank building. They LOVE the downtown radio tower. A noisy bunch during the summer Farmer's Market when they sit up there and squawk! I believe they've nested on the Southside cliffs as well.” And a story in mylittlefalls.com reveals that raptor expert Deborah Saltis has been here to check on them and, among other things, clarified that “the Eastern race of the peregrines went extinct due to pesticides, which made the eggshells thin so that their nesting failed. The peregrines we now have are a mix of three races, European, the Western part of the United States, and Canada,” she stated, adding, “They’ve made an amazing comeback.” So maybe our locally adapted birds have a happier ending than the ones in this book…

I am going to take to heart this passing remark from Baker, “Hawk-hunting sharpens vision.” Wish me luck, wish them luck.

And so, I have questions. This book might provide answers, contingent on it being about the British species and a different habitat. Though I do understand that peregrines are found almost all over the planet. While there is variation, a peregrine will have dark “sideburns” on its fierce face (I’m sorry but I think of Mister Darcy/Regency era gentlemen), and banded feathers on its chest (the adults). These are not huge animals. A male, called a “tiercel,” may be 16 inches long and weigh under 2 lbs., while a female “falcon” is perhaps a third bigger.

Their eyes see with impeccable detail. They’re significantly larger and heavier than human eyes. The author explains: “where the lateral and binocular visions focus, there are deep-pitted foveal areas; their numerous cells record a resolution eight times as great as that of a human retina.”

What do they eat? (See next paragraph.) Where do they nest or establish eyries? (High cliffs; as we have here in this valley; the tall buildings make a reasonable substitute. They make a “nest-scrape” for their eggs.) Are they the fastest animals in the world? (Baker says 100 mph or more, but the internet says 240 mph! Making the answer, I gather, yes.) Do crows harass them, or are the two species playing or skirmishing? (The two birds are approximately the same size, and do spar, but at least in the pages of this book, peregrines can elude and outfly crows when they wish.) Other factoids? They bathe every day (to rid themselves of lice), so a water source is a must, ideally accessed from a slope and at least 6 inches deep. Moulting, going from juvenile to adult feathers, takes up to six months, proceeding faster in warmer weather.

Peregrines are deadly killers, that’s the main takeaway from this book. And other creatures know it and alarm, evade, hide, cower, or panic; Baker speaks of the “unmistakable spoor of fear” when a peregrine is sensed. Typically they kill by swooping down—or up from under (element of surprise)—on other birds at high speed, 100 mph or more, wings tight against their body, lethal talons ready. This lethal dive is called a “stoop.” They disable or usually outright slaughter prey. Piercing and slashing the victim’s body with their sharp talons, later breaking the neck to be sure, plucking off feathers in the way, and then tearing off and gobbling most of the flesh. Often leaving behind wings, feet, beak uneaten. They can and will kill other raptors such as kestrels and sparrowhawks; they can and will kill creatures larger than them. They may also consume mice, rabbits, and other small animals, and the occasional worm or insect. But other birds are their main diet.

Happening upon a kill is, Baker says, like encountering “the warm embers of a dying fire” (I shudder, chilled). His descriptions are not sanitized; they are detailed and harrowing. A few samples:

“It was almost dark when I found the remains…the feathers and wings of a common partridge, lying on the riverbank…blood looked black in the dusk, bare bones white as a grin of teeth.”

“He mounted like a rocket, curved over in splendid parabola, dived down through the cumulus of pigeons. One bird fell back, gashed dead, looking astonished, like a man falling out of a tree. The ground came up and crushed it.”

“The duck landed but the drake flew past. Suddenly realizing he was alone, he turned to go back. As he turned, the peregrine dashed up at him from the marsh and raked him with outstretched talons. The teal was tossed up and over, as though flung up on the horns of a bull. He landed with a splash of blood, his heart torn open.”

Not surprisingly, although gradually (like gaining altitude), the earthbound human with binoculars begins to merge somewhat with his quarry, so intent is his pursuit. He knows it and he yields to it. He ceases to walk, says instead “I went along,” or “I moved on.” One day he spontaneously remarks “Nothing is as beautifully, richly red as flowing blood on snow. [a pause] It is strange that the eye can love what mind and body hate.” More slippage: “I avoid humans, but hiding is difficult now the snow has come…I use what cover I can. It is like living in a foreign city during an insurrection.” Another day, unable to find the peregrines, he pauses in a field, shuts his eyes: “I tried to crystallize my will into the light-drenched prism of the hawk’s mind. Warm and firm-footed in long grass smelling of the sun, I sank into the skin and blood and bones of the hawk. The ground became a branch to my feet, the sun on my eyelids was heavy and warm. Like the hawk, I heard and hated the sound of man, the faceless horror of the stony places.” Candidly, humbly: “there is a bond: impalpable, indefinable, but it exists.”

This book spans seasons, autumn into winter into spring (after which peregrines depart/migrate). Autumn reminds the reader that humans with guns kill birds, too. Winter snow, ice, and cold remind the reader that food grows scarce and that some creatures die of natural causes, freezing and starving. The peregrines kill more in winter, if they can, just to get the same amount of calories they’d get in better weather. Spring brings welcome warmth, abundant life in all forms, but also farm chemicals. Baker’s outrage and grief is piercing— “foul poison burned within them like a burrowing fuse. Their life was lonely death, and would not be renewed…they were the last of their race.”

Why save or mourn such vicious killers? someone might wonder. Anyone with a sense of how ecosystems work wouldn’t ask.

Also can’t we simply be awed or humbled by their magnificence? Peregrines know and see and navigate things we can barely guess at, they are “of the wind, it is their element, only within it do they truly live.” We, though alive, cannot join them, can never feel what they feel or do what they do.

Over open parkland he found another thermal and circled within it till he was very high and small. From a great height he slanted gently down above the common, falling slowly to the skyline. Then he rose once more in a steep, flickering helix, hypnotic in style and rhythm, his long wings tireless and unfaltering. He shimmered and coiled and dwindled away over the sharp-spired hill, and was descending beyond it when distance suddenly quenched him. He left the blue sky baroque with fading curves of power and precision, of lithe and muscular flight.

Sometimes, often, I think about the inadequacy of words, but the author of this book strove and strove, letting the words flow, using them boldly. Coupled with his urgent commitment to follow, observe, and understand the peregrines, his prose is bracingly poetic. I do not believe he was showing off or romanticizing. Rather, he was earnestly, honestly, deploying his resources. My god, some of these passages are just stunning. And just when the reader is feeling saturated with all the information, adjectives, similes, speculations, and metaphors, he lays it down bluntly: A peregrine is beautiful.

Sarah Moss, Names for the Sea: Strangers in Iceland

“To drive from Stykkishølmur to Akureyri feels like passing through geologic time. We take a gravel road around the coast, bumping and leaping through an exaggerated Alpine landscape with a few Norwegian fjords cut-and-pasted around the foothills. There is no other traffic, no people, but grass and blueberry bushes and low birches massing on the hillsides. Streams glitter across the valley in the sun. The fjord is full of swans, and sometimes sheep wander into the road. Birds call. We go on, and up, and up, and down, Guy driving and the rest of us watching the land as if it’s some new kind of technology we’ve never seen before.”

For the author, for me, and for the friend who gave me this book, Iceland has an eerie and seductive fascination. It seems both harsh and gorgeous. The extremes of light and dark over the course of a year—and the author and her family (hubby, two small boys) do spend an entire year/a visiting professor in Reykjavik. The volcanic landscapes, lava red and moving or black and frozen in place, days filled with brown air and ash. The people (women and men) who knit, in the allegedly egalitarian society. The rugged mountain peaks. Hot springs, sea birds, geysers. Rumors of elves or trolls, presumably hearkening to the Viking/Norwegian folklore of Iceland’s earliest settlers.

I have passed through Keflavik airport, coming and going from Europe, always in the summer months. Remembering “Greenland is icy and Iceland is green,” I pressed my face to the small airplane window and peered out curiously. From the air, from that approach, Iceland looked neither icy nor green, but barren and treeless (lots of yellow-flowered bushes I thought were gorse; plus abundant scrubby light-purple lupines of some kind). The nearby Blue Lagoon, with its aquamarine, steaming water, is sprawling, perfectly visible, and it beckoned, as it no doubt does to many tourists. Our eight-hour layover was overnight and, eager as the Blue Lagoon is for tourist money, no shuttle buses run in those hours. Disappointed to miss that, we tried to nap, with our carry-on backpacks for pillows and our jackets for blankets. But at 2 am, the summer sun bright in my eyes, I gave up on sleeping and walked around while Al dozed more successfully. Keflavik knows it is a way-station, a hub for small-size jets for those traveling between North America and Europe, but it aggressively markets Iceland as a destination. The airport walls are plastered with mural-size photographs of beautiful blond people with braids and colorful sweaters, with images of wild waterfalls and fiery lava streams, with alpine meadows full of wildflowers. Oh my, I thought, groggily contemplating all this beauty. There’s a store called 66º North, full of handsome outdoor gear (we’re almost to the Arctic Circle!) and a Blue Lagoon shop offers cosmetics like genuine Icelandic mineral bath salts and lotions derived from lichens and seaweed. The food concession had an abundance of what appeared to be a local yogurt, called Skyr. Oh my to all of this!

Downstairs, dimly lit, had closed rental-car agencies. I paused before one to study the large map on the wall behind the counter. The highway that encircles the island nation, Route 1, is aptly called the Ring Road. Emblazoned across the center of the map, obscuring Iceland’s mysterious interior, is a stern warning in many languages, to the effect of “those who rent vehicles from us are forbidden to divert from the Ring Road.” Huh! I muttered. Well, I would! Isn’t the national park where two tectonic plates are splitting apart and steam and lava hiss forth, isn’t that in the middle? Not to mention, a tourist like me might want to explore a side road to see “the real Iceland.” Of course, these days, a unobtrusive tracking device attached to the rental car would probably bust me. I also sense now, now that I’ve read this book, that those interior roads are probably actually barely passable tracks full of rocks, ice, and lava fields. Especially if the main road, the good road, is composed of gravel in many places, yikes. (A few years back, I read an article in Newsweek recounting how a new road proposed across the interior—to spare tourists as well as Icelanders from having to do the full drive—was defeated. Not because it went through remote, rugged landscapes, not because the project would destroy fragile plant or animal communities, but because it passed through troll habitat. The trolls would fuck with the tourists before the sharp hardened lava had a chance to lacerate the rental-car tires. The trolls would punish the Icelanders for sacrificing wilderness to tourism.)

I’ve also been so captivated by dramatic landscape photographs of rural Iceland. The cold blue-green sea, the waterfalls, sky, rock, seabirds, sunlight, twilight, Northern Lights, ice, lava. Someone mentioned to me that some of the Game of Thrones episodes were filmed there; the “lands beyond The Wall” as well as other vast, sprawling settings—I believe it. In fact, the extract above captures what I imagine or would expect, if I could ever travel there as a destination. Last but not least, I’ve read a other books set in Iceland. Both had protagonists whose ancestors had left for more hospitable places like the upper Midwest of the United States: The Windows of Brimnes by Bill Holm left me with an abiding impression of his solitary summer cottage way up north among cliffs and screaming seabirds and crashing seas; The Tricking of Freya by Christina Sunley, which among other things, filled me with awe for Thingvellir, the national park I alluded to above.

So, this long preamble is just to orient me, take stock of what I thought I knew, and to travel in the pages of a book once again to this enticing place.

Sarah Moss also had these fascinations and had traveled around Iceland, on a shoestring budget with a buddy when they were just 19 years old. When she was offered a one-year teaching job many years later, she seized the chance to return. “Travel writers are always writing home,” she opines to her students in a class on travel writing (her syllabus included the great Jonathan Raban, of course/he’s also an adventurous Brit)—but of course, that view is also the exercise of this very book.

A less-romantic portrait emerges. Iceland is not a gorgeous, flawless physical or social paradise. Her frame of reference is always, of course and necessarily, the England left behind, which isn’t perfect or idealized either. Iceland is, of course, totally different, in obvious and subtle ways. She describes what she sees and learns, she asks questions, she’s frank.

For starters, finding short-term housing is tricky and strange. She and her family arrive shortly after the banking crisis and, after a lot of trouble and the leveraging of any and all local connections, get a rental flat in Gardabaer, a Reykjavik suburb. “The building is on the corner of a development that was half-built when the banks collapsed and the money ran out, and it’s still half-built, as if the builders had downed tools and walked away one day in the winter of 2008…no-one else lives in our building.”

Getting around the city is not easy. Residents don’t walk or much use the buses; instead they favor huge vehicles, hummers and SUVs, drive like maniacs, and never use turn signals. The drivers are so reckless and aggressive that she and her husband try avoiding the acquisition of a vehicle (also to save money; her salary is now worth half what it would’ve been). She rides a bike to her school. They bundle up their boys when they go out and push the younger one’s stroller through pedestrian-unfriendly areas—in fact, a lava field, and later, slush and snow and strong winds, to get groceries and do other shopping. When they finally realize, especially with the onset of the long, dark, frigid winter, that they need to get a vehicle, finding a used one is a frustrating process. Icelanders don’t buy and sell used goods, it seems, not even clothing. (One woman relates how she actually destroyed an item of furniture when she upgraded to a new one; reusing other people’s stuff is considered gross/just not done.)

Speaking of groceries, not surprisingly most everything is imported and expensive. The vegetables and fruit are of miserable quality, except for a brief spell in summer when hothouse-grown greens are in some markets. Traditional Icelandic food seems to be a lot of salted and smoked fish (haddock) and meat (especially lamb). On one hasty trip, she accidentally buys and brings home whale meat; she never tries puffin breast (I don’t think I could either). She has mixed feelings about smuggling in her favorite food items, treats, and spices after a Christmas trip back to England, but she does it anyway.

She is captivated by Mount Esja, the mountain that hovers over Reykjavik the way Mt. Hood hovers over Portland, Oregon or Mt. Rainier over Seattle. She notes its colors and moods, and occasional disappearances due to weather or volcanic smoke. However,

I leave work early to catch the last of the slow purple sunset on the way home. Cycling along the peninsula one afternoon, I look back at the city and see that there is a pale green mist hanging over it, filling the space between Perlan and the church at Seltjarnarnes and trailing out over the sea beyond. At first I take it for another Arctic natural phenomenon—it has a beauty of a kind, this strange colour wrapping itself around the city’s landmarks and hovering on the lower slopes of Esja, as if the Northern Lights have somehow crept out by day—but…[it’s] not aurora but smog, “because there’s not enough wind.”

The city at the foot of this magnificent mountain is sprawling and has big stores like IKEA and Toys R Us, that is, it is not particularly historic or charming (I’m thinking of Anchorage, Alaska, another uninspiring urban area in a magnificent setting). She uncovers and comments on the ways education—her job, as well as her kids’ preschools—is different from what they are accustomed to. She and her husband pull one of their sons out of a kiddie school here after a couple weeks because the genders are segregated and the roles are so rigid (boys build things, girls clean, etc.) Her (mainly Icelandic) adult students balk at being asked to tell second-hand stories—interviewing another person, for example—and don’t like to talk in class for fear, another professor explains, of appearing foolish.

She tries hard to uncover what is uniquely Icelandic. They visit the island Heimaey where most of a village was devastated by a volcanic explosion as the residents did a hasty by-boat evacuation. In winter. In a storm. She inquires about knitting and the iconic Icelandic sweater (whose history, it turns out, is only a generation or two old). She interviews people who lived through the world wars and saw foreigners and warships come and go, and weathered the economy ebbing and flowing. She even drives out to meet a woman in a remote valley who is an expert on “the hidden folk.” She is respectful, but candid in her impressions and about her limitations (her biases; not enough time). It’s all so interesting.

Her writing is frequently gorgeous, I have to say. I can see, almost feel, what she is experiencing. I loved this passage (below). Hyperbolic? Maybe not, if you are there and paying attention?

Winter sunsets, like summer sunrises, go on for hours. The sun sidles over the horizon, but the sky stays pale for a long time. I walk the coast path long after the last light has drained from the sky and think about darkness, and I like it. I like the way it’s impossible to ignore the passing of time. Today is darker than yesterday, tomorrow will be darker than today. Dust we are and to dust we shall return. It makes me feel alive, makes me feel my life like heavy cloth on my hands.

The thing that interested me most in this book, though, turned out to be how she navigated being a outsider. How, in the short time they lived there, she sincerely and diligently tried to get a handle on the place. How she tried to savor what is good. How she felt, and how her feelings and assumptions and perceptions evolved. How she made friends. (Missing or glossed over, though, was her husband’s experience. She was the breadwinner, and clearly also devoted a lot of time to this book, or the notes for it, as well as her full-time job. Well, maybe she was protecting his privacy, maybe his story is not hers to tell. Still, including more about him, and them, might’ve painted a broader picture of what it’s like to move as a family to a foreign country.)

I have been—by chance and by design—a short-timer in a few places in my life. If we always lived like we might leave soon, we could really look, listen, and really learn. And we might still see and expand upon what attracted us in the first place. And still, here’s the catch, we would not be done. The opening extract here is from a trip they took after they had moved back to the UK and returned to visit, for there were, of course, unfinished things like a roadtrip to the north. She ends with “I’m still not ready to leave Iceland.” I get it.

Louise Penny, A Better Man

“She wasn’t interested, but you continued to harass her.”

“I wasn’t harassing her. She was afraid.” Cameron shot a filthy look at the man across the bistro. “She wanted to leave him, I could tell. I was just trying to help her break away.”

He lifted his head and met Gamache’s eyes. “I love my wife. I have two children. But there was something about Vivienne. Something…” he stopped and thought. “Not innocent. Not even fragile. She seemed strong, but confused. Beaten down. I just wanted to help her.”

“Gamache looked at Cameron’s face. Disfigured. And knew how deep the blows went. How deep the disfigurement went. And knew how much this man, while a boy, would have wanted someone to help him.”

“The best book yet in an outstanding, original oeuvre”—Wall Street Journal, so says the cover. I don’t agree; the superb A Great Reckoning is the standard to meet in this series IMO. I dunno, this one just didn’t go real well for me, even though it was clearly carefully crafted. Maybe a bit too much telling rather than showing? Her distinctive choppy writing style grated, even though I recognize how it amps up the tension. The mystery was knotty and frustrating and dragged on, for Gamache and his colleagues, but also for the restive reader (though one could argue that this is realistic). Also, WTF, a person of his rank invites a stranger, the murdered woman’s distraught father, to stay in his home?! How unprofessional is that?

Also, the murdered woman was abused, so a smart and (understandably) bitter woman who runs a shelter is consulted by the detectives. And yet in the Acknowledgments, the Clintons are among the people Penny thanks (I am thinking of Hillary’s victim-blaming in defense of Bill). Minor point, I’ll grant, and yet, perhaps a bit, err, dissonant?

Sprinkling in a Melville quote repeatedly (all truth, with malice in it), even when identified, felt labored. Could’ve cooked the whole meal without it.

Mitigating, however, was a passing but well-deployed quote from Anne of Green Gables by Clara, “I’m well in body, but considerably rumpled up in spirit”! Speaking of Clara, it was hard to swallow that her art career was being dramatically tanked overnight by mean tweets, to the extent that buyers wanted to return past works! and that a heavyweight NYC critic actually traveled to Three Pines to assess and judge (getting unexpectedly charmed by the bistro and village, naturally). Even though it’s true any artist can create poor or lazy work and have to be nudged into understanding/reckoning with that and then rebooting. Just, uhh, not like that.

Not nearly enough vivid descriptions of the bistro breakfasts, either. Why, Olivier didn’t bring forth cafe au laits and warm almond croissants till, what, page 420?!

I just felt scant joy in this book and wonder if the author didn’t either. Of course, it’s a homicide mystery, but anyone who follows this series avidly knows what I mean here. Le sigh.

Mitigating, though, are moments like the conversation extracted above. Why do people go into “helping” careers? Armand Gamache knows, Louise Penny knows.

Keith Miller, The Book of Flying: A Novel

“ ‘All is rumor. It’s why we write, it’s why we sing, it’s why we make love here in this city, enraptured and captivated by fear. For generations we have lived with the knowledge that some must ascend to the dark castle that the rest may live this life of love and song, fine food, stirring literature.’

‘But don’t you want to be free?’

‘Why do you think I write?’ She tapped the chapter he’d been reading. ‘I travel far from this city’s winding streets in these pages.’

‘And you never get lonely cooped up with your manuscript?’

‘Lonely? Sometimes I can hardly sleep my characters chatter so, clamoring to have their voices immortalized.’ ”

Honestly, I was a bit torn about this book (but it won me over). My reserve began with the subtitle, “a novel.” Just in case you thought you were buying a book about how to pilot a small aircraft? Of course it is not. It is a lush, fanciful tale about Pico, a solitary poet-librarian, who is in love with Sisu, a winged girl. His parents, too, were winged, but as sometimes happens, wings were not passed to him. The youngsters live in a city by the sea where about half the residents are winged and half are not. He learns—by intriguingly hidden message wedged into the floor of his lonely library (he is not the first curator/it is old)—that he can acquire wings, if he makes an arduous journey to a place on the other side of a dark and mysterious forest and a scorching desert, to the “morning town of Paunpuam.” This he decides to do. I had to page back later to discover whether he alerted the girl of his heart. Oops, he did not. So we can guess how this guileless Odysseus’s story will go.

It’s also a book about loving books, loving literature and poetry. In fact, before Pico sets out he surveys his library, knowing he must leave it all behind, but wanting to bring a few favorites along. His choices are: “a book of poems, a dense novel, a volume of queer stories.” These selections stay with him a long time, through all sorts of trials and mishaps, and are joined late in the tale by a plain book that he writes and transcribes in. Hmm. Pretty thorough. (And I, like any reader of this tale, pause to ask myself which ones I would choose if I was traveling light…) Down the line, he will get a chance to visit other collections and bookstores, and to read a portion of a book that features a visit to a planet of books, where everything is made of books, they are nourishment and beds and companions and creatures, even insect-size. Yeah, the telling’s all a bit self-regarding, but I think our author is in earnest and it’s endearing (if that doesn’t sound too patronizing).

Not too far along on his trek, Pico finds himself in the arms of Adevi, a beautiful, passionate, deadly Robber Queen. My first clear clue that this is not a child’s book, LOL. “I’ve betrayed her,” wails our hero after this formidable woman takes his virginity. “Climb down out of your brain, poet,” she says tartly, “You’re tangled in the cobwebs of your dreams. Welcome to the land of your body, with all its guilt, all its ecstacy.” A bit of time passes before he crawls to her bed and says simply “teach me.” Oh lordy, I eyerolled, am in for a repeat/version of Kvothe’s tedious, repetitive sexual education in Patrick Rothfuss’s Wise Man’s Fear? Fun for the horny, self-indulgent male fantasy author but not really for my reading pleasure, sigh. I’m with Adevi. Live in the moment, love the one you’re with, learn, live your life, yada-yada.

Other lovely lovers appear in later chapters. My favorite was the quirky, solitary whore Narya, who loved books and reading and writing as much as Pico (see extract of one of their conversations, above) (though, why did she have to be a whore? why not, oh, a waitress?). “What it is to encounter one’s passion in another.” Here is your match, blundering dude, I muttered. Even the author favors Narya, I think; on the back of the title page, a fragment of a Rilke poem is credited and given to Narya. That is highest honor, IMO.

But among the artifices and challenges tossed at our hero, the book had some moments that went beyond contrived or entertaining, uncovering or dislodging relatable moments and musings. In the city where he befriends Narya and others, Pico gets a little too comfortable, settles in, and abandons his quest. He takes his eyes off his goal, learns to love, works, finds community, “nests,” and feels the ups and downs and pangs of embedding in a place. Like the extract I chose suggests, these things are actually worthy and a way to live, even if (or especially if) trapped by circumstance, geography, or fear.

As in any journey, there are times when Pico doesn’t know what to do or where to turn. His arrival in that city, in fact, is rendered in vivid detail. He’s cold, he’s hungry, he’s disoriented, everyone is busy and knows one another, nobody sees him, he’s at loose ends. Have you seen that person on the streets where you live and work? Have you been that person? When, much later, he makes his stumbling way across the dry, hot desert and runs out of water, relief or rescue also seems elusive or impossible. And yet the wheel turns. It’s a fantasy that his suffering is alleviated, sure, but by cycling through that at least twice, Pico should learn. Reflecting on these two essentially similar and stressful scenarios, I thought about how, really, we never can make it on our own, and I thought about the times when help is, truly, mercy and grace. How extra-sweet a warm bed or a kind touch or food or water is, after deprivation. That he flies away alone on the last page, then, made me sad.

Before I leave off here, I also want to note that the author’s fascinating bio caught my eye. There he is on the inside back flap, a young, fresh-faced, bearded white guy, “Keith Miller is an American who was born in Tanzania, raised in Kenya, and wrote this novel while living in southern Sudan. He now lives in Egypt, where he is a design consultant and art teacher at a center for refugees.” (What on earth makes him American, then? Just his name…?) The people and the landscapes in the book suddenly seem to be ambitious acts of interpretation and imagination.

Also. I grabbed this book off the shelf here in our second home, on an rugged island off the southwest coast of Nova Scotia; I have no idea what it is doing here or how it washed up here. An unsigned Christmas tag is tucked inside, “For the house where books and stories live…” I do not remember receiving this book as a gift and don’t recognize the handwriting. Strange indeed. Well. Stories get around.

Thomas Hardy, Tess of the D’Urbervilles

“The gaiety with which they had set out had somehow vanished, and yet there was no emnity or malice between them. They were generous young souls; they had been reared in the lonely country nooks where fatalism is a strong sentiment, and they did not blame her. Such supplanting was to be.”

Ohhhh. Long sigh. Scarcely have I ever read such a sad story. Tess, who was blessed with beauty, intelligence, a fierce work ethic, and a beating heart, was unfortunate to be born into poverty in rural England in the late 1800s (the novel was published in 1891). Small pleasures intervene here and there—birdsong, a lovely view, laughter with friends, being competent at her work, picking flowers, and even falling in love—but mainly hers is a tragic tale. Rape at an early age, death of the infant (tellingly, she names it Sorrow), toil, confusion, pressure and compromise, and a final desperate act that leads to her death by hanging (she murders her rapist). Employers grind her down, family obligations press on her, her rapist stalks her, her husband deserts and disappoints her. Breaks her heart. All escapes are blocked.

The extract I chose above is from a scene where she is hanging out with other women, other farm laborers. They all have a crush on the same fellow, an upper-class young man who is doing time at the farm in order to learn farm management, but he favors Tess. He will eventually become her husband, but this will neither elevate her socially or economically, nor will the alliance help her escape her sad past. In the end, all escapes are blocked. Fatalism indeed.

Thomas Hardy was up to more than laying out and decrying the poor choices available to poor women in that place and time (Tess’s life and circumstances are much more grim than that of a Jane Austin heroine). He was up to more than suggesting that beauty and intelligence above one’s station are curses (he may or may not be as sexist as his male characters) …But I give him credit for telling a woman’s story in the times he lived in. Limning the tale is the emerging industrial revolution, which already is putting an end to a culture, a place, a way of life. Tess simply couldn’t navigate, despite her best efforts. Hardy paints a more general and bleak picture of a culture degrading into dehumanization; this, I wager, also made the book difficult/controversial for his contemporaries.

Thoroughly depressing.

Jane Smiley, Perestroika in Paris

“Sunny days were few and far between lately, but Paras didn’t much mind the rain. It was easier to live outside in all weathers than it was to be confined to a dark stall, unable to see much, but hearing every little thing, day and night. All the horses complained about being cooped up, even the least curious ones. And then, when the humans took you out, they got spooky when you were startled by something. The better riders just sat there, and said, “Ah-ah,” but a sensitive filly like Paras could feel in her very bones that that their hearts were pounding. If you lived out, there wasn’t much that surprised you. Paras could see things all over the Champ de Mars—humans large and small, dogs large and small, birds of all kinds soaring and swooping. If you lived out, every noise had a reason, every sight a before and after. No surprises…”

Oh! What a unique, entertaining, adorable novel! It even has a happy ending, and sometimes we just need that…so rare in this troubled world of ours.

I’ve never read anything quite like this little book—an adventure from the point of view of an animal, a race horse named Perestroika, “Paras,” and some friends she makes after she walks away from the barn and ends up sheltering at the big public park in Paris. “Paras in Paris,” I tried it aloud and smirked, though the author just drops it there. The new friends: a wise but lonely dog (Frida), an old, somewhat arrogant raven (Raoul), a pair of plucky ducks (…wait for it), plus a few assorted humans.

Certainly I’ve heard of Jane Smiley; she’s a highly regarded author who won a Pulitzer for a book called A Thousand Acres, which is set on a Midwestern farm but I understand is loosely based on King Lear. I may have to investigate it, but I wager that book is much heavier-going. It was obvious from the start of this one that I was in the hands of a master storyteller and my appreciation only deepened as the tale unfurled. It is entertaining, even laugh-out-loud funny in spots, but it is not frivolous, not a kiddie book. Nobody is mocked or a parody. Even the raven isn’t a cliché. The humans, though less prominent, are…human.

The build-up to the nifty ending somehow never veers into sentimentality or total predictability, even as it satisfies. This is just a fine tale, very finely told. And, as a Los Angeles Times reviewer quoted in the opening papers remarks, “In an era beset by polarization and even violent tribalism, it feels like a gift to find a novel in which characters of different species—with different desires and instincts—come together to build a community.” Consuming this book felt like dining on nourishing comfort food.

The laugh-out-loud moments chiefly came from the birds. The duck pair are called Sid and Nancy—ha! Sid is shrill and obnoxious; Nancy is tart and pragmatic. Late in the book, on a migration return trip back to Nancy and the latest batch of ducklings (males always take off, it seems; I first learned this in Make Way for Ducklings), he shares, well, prattles, his fresh thoughts with Raoul after some time away:

“Every summer is a new beginning, that’s what I’ve learned. I don’t have to carry the past with me. My approach to the dangers of reproduction is my choice. I am in charge of who I am and how I view things. I own my fears.”

“That’s a wise—”

“I’ve had my eyes opened. We had many group discussions as we were migrating, and I was given to realize that certain experiences I had as a duckling have a strong impact on my world view…” [on and on in this mode for a bit] …“I’m glad we’ve had this talk,” said Sid.

“Yes,” said Raoul.

Who among us cannot relate to such a conversation? Jane Smiley is subtle but I saw what she did there. The Los Angeles Times reviewer is spot on: the deeper meaning is about forming community. A bunch of loners (humans, too) traveling through daily life in close proximity discover, form, and benefit from community. Even self-absorbed Sid.

J.D. Salinger, “For Esmé, With Love and Squalor,” from Nine Stories

Addendum: I only realized a day later that I had finally been moved to pick up and read this story on Veteran’s Day (Remembrance Day). Not a coincidence, I have to believe, but one of those subterranean confluence things that happens now and then.

“About the time their tea was brought, the choir member caught me staring over at her party. She stared back at me, with those house-counting eyes of hers, then, abruptly, gave me a small, qualified smile. It was oddly radiant, as certain small, qualified smiles sometimes are.”

What in the world brought me to this book, and this particular story? Well, there’s a story behind it. One day, between tasks, I was standing briefly in my small “Red Corner” room, which consists of a window, a big bookcase, a small bookcase, and a beloved rocking chair, as well as some mementos (a tray full of seashells from Monhegan Island, Maine, from Bean Hollow State Beach south of Half Moon Bay, California, and of course some from Brier and Long Islands, Nova Scotia), pix of my sons, and so on. This small, admittedly cluttered space is my Linus blanket and my nexus. But on that day and in that moment, I looked critically at it. Too many books! Piles on the floor! Books I read long ago and have outgrown or didn’t like! Time for a purge. I quickly filled two large cardboard boxes, with little or no remorse. More recently acquired books found places on the shelves at last. Ah!

One of the discards was this book. I’ve had it for ages…decades. Have I ever even cracked it, read any of the stories? Am I even a J.D. Salinger fan? Good grief. Why hang on to it? But it didn’t fit in the stuffed boxes so I laid it on top. A few nights later, having finished some other book (see below, somewhere down there), I thought to myself, “Why not read a short story tonight? Rather than starting a new, substantial book right away?” I settled in and thumbed through. It was dusty and the years had not been kind to the cheap paperback: the pages were stained, browning, brittle. “A Perfect Day for Bananafish.” Baffling and dull. “Just Before the War with the Eskimos.” “Uncle Wiggly in Connecticut.” Baffling and dull. Who cares? Insipid, flaccid, almost plotless, and everyone smoking cigarettes like some old movie, so just … meh. Why bother? Back onto the discard pile the book went. Evidently his writing doesn’t age well, I thought. (I remember seeing “Easy Rider,” for the first time—being too young in the 6os—in the Brattle Theater in Cambridge in the late 1980s. Everyone in the audience, including me, laughed or twitched or cringed at the once-groovy parts. The disconnect with Salinger’s stories here felt much the same. Embarrassing now.)

Then, on a Facebook page that ebbs and flows with activity, Bard Writes, the moderator tried to rouse the Bard alumni who subscribe. “What are you reading this weekend?” she prodded. I took the bait, fresh off the above thoughts, and briefly slagged Salinger. Well. A few days passed and when I checked in on Facebook again, someone had responded. He wrote:

I read "Bananafish" when I was about thirteen, didn't get it, never went back until this week. And still don't get it. I don't get most of the stories in the collection (except "Esmé", which is downright touching and apparently spoke to many soldiers of the era returning with inner wounds).

I agree that many of the characters are hard to relate to (except perhaps as our parents in other times) today, not to mention the lavish use of cigarettes - which brands, how they hold them, what containers they use, ashtrays, spilling ashes... Screams "another world" today.

I feel about Salinger as I do about Eudora Welty - there's no doubt this is excellent, authoritative writing (though I find Welty's characters more engaging, perhaps precisely because they are so exotic to an urban Northerner), but generally, I have NO IDEA what's going on. I don't know what the central problem is, I don't know how it's resolved, I don't discern a necessary structure. I don't know, for instance, how Teddy's standing on something at the start of that story relates to his holding forth on a deck chair later, never mind the ending. A lot of the pieces seem structurally arbitrary, if intriguing.

Nor am I convinced by the glosses I've seen on several of these stories elsewhere. I really feel like the critics are straining to find meaning and structure beyond what the text supports.

It might be fun to do a whole thread on great works we find incomprehensible (James Joyce would probably top the list), yet feel we, as aspiring writers, should at least TRY to read. Salinger, for instance, apparently influenced a number of other writers I DO follow, so clearly they found something I'm having trouble grasping. And of course even if one doesn't "get" a writer, in the sense of deciphering a puzzle, simply being exposed to good style can be beneficial.

Helpful, interesting, thoughtful (I’d like to have more friends like him, frankly). However, the discards-project stalled and I got distracted and now a few months have gone by and I finally, finally moved the boxes down to the front hallway this evening. They go off to the local library’s donation bin, or get stuffed into a Little Free Library this week, by golly. Oh. There’s the Salinger again. Okay, mister, I’ll try one last time; I’ll read “For Esmé.”